Cross Origin Resource Sharing (CORS)

important

This tutorial assumes you have a good working knowledge of HTTP. If you don’t read the HTTP tutorial first.

Back in the early 2000s, web browsers started allowing JavaScript to make HTTP requests while staying on the same page: a technique originally known as AJAX, but today is known as the fetch() function. This was very exciting because it transformed the web browser from a mostly static information viewing tool into an application platform. We could now build rich interactive web applications like those we had on the desktop, but without requiring our customers to run an installer and keep the application up-to-date. The browser just automatically downloaded and ran the latest published version of our web application whenever our customers visited our site.

But the browser vendors faced a difficult question: should we allow JavaScript to make requests to a different origin than the one the current page came from? In other words, should JavaScript loaded into a page served from example.com be able to make HTTP requests to example.com:4000 or api.example.com or even some-other-domain.com?

On the one hand, browsers have always allowed page authors to include script files served from other origins: this was how one could include a JavaScript library file hosted on a Content Delivery Network (CDN). Browsers also let HTML forms POST their fields to a different origin to enable “Contact Us” forms that posted directly to an automatic emailing service.

On the other hand, there were some very significant security concerns with allowing cross-origin requests initiated from JavaScript. Many sites use cookies to track authenticated sessions, which are automatically sent with every request made to that same origin. If a user was signed-in to a sensitive site like their bank, and if that user was lured to a malicious page on evil.com, JavaScript within that page could easily make HTTP requests to the user’s bank, and the browser would happily send along the authenticated session cookie. If the bank’s site wasn’t checking the Origin request header, the malicious page could conduct transactions on the user’s behalf without the user even knowing that it’s occurring.

Not surprisingly, the browser vendors decided to restrict cross-origin HTTP requests made from JavaScript. This was the right decision at the time, but it also posed issues for emerging web services like Flickr, del.icio.us, and Google Maps that wanted to provide APIs callable from any web application served from any origin.

Several creative hacks were developed to make this possible, the most popular being the JSONP technique. But these were always acknowledged as short-term hacks that needed to be replaced by a long-term solution. The great minds of the Web got together to figure out how to enable cross-origin API servers without compromising security. The result was the Cross-Origin Resource Sharing standard, more commonly referred to as CORS.

How CORS Works

The CORS standard defines new HTTP headers and some rules concerning how browsers and servers should use those headers to negotiate a cross-origin HTTP request from JavaScript. The rules discuss two different scenarios: simple requests; and more dangerous requests that require a separate preflight authorization request.

Simple Requests

Simple cross-origin requests are defined as follows:

- The method is

GET,HEAD, orPOST - The request may contain only “simple” headers, such as

Accept,Accept-Language,Content-Type, andViewport-Width. - If a

Content-Typeheader is included, it may only be one of the following:application/x-www-form-urlencoded(format used when posting an HTML<form>)multipart/form-data(format used when posting an HTML<form>with<input type="file">fields)text/plain(just plain text)

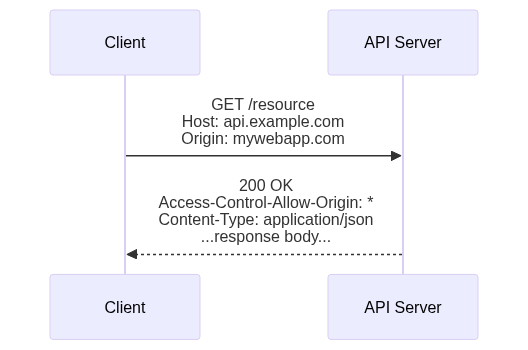

If JavaScript in a page makes an HTTP request that meets these conditions, the browser will send the request to the server, adding an Origin header set to the current page’s origin. The server may use this Origin request header to determine where the request came from, and decide if it should process the request.

If the server allows the request and responds with a 200 (OK) status code, it must also include a response header named Access-Control-Allow-Origin set to the value in the Origin request header, or *. This tells the browser that it’s OK to let the client-side JavaScript see the response.

This Access-Control-Allow-Origin header protects older servers that were built before the CORS standard, and are therefore not expecting cross-origin requests to be allowed. Since this header was defined with the CORS standard, older servers will not include it in their responses, so the browser will block the client-side JavaScript from seeing those responses.

This made sense for GET and HEAD requests since they only return information and shouldn’t cause any changes on the server. The inclusion of POST was a bit problematic—it was added to ensure that existing HTML “Contact Us” forms that posted cross-origin would continue to work. This is why the Content-Type is also restricted to those used by HTML forms, and doesn’t include application/json, which is used when posting JSON to more modern APIs.

Supporting simple cross-origin requests on the server-side is therefore as easy as adding one header to your response: Access-Control-Allow-Origin: *. If you want to restrict access to only a registered set of origins, you can compare the Origin request header against that set and respond accordingly.

Preflight Requests

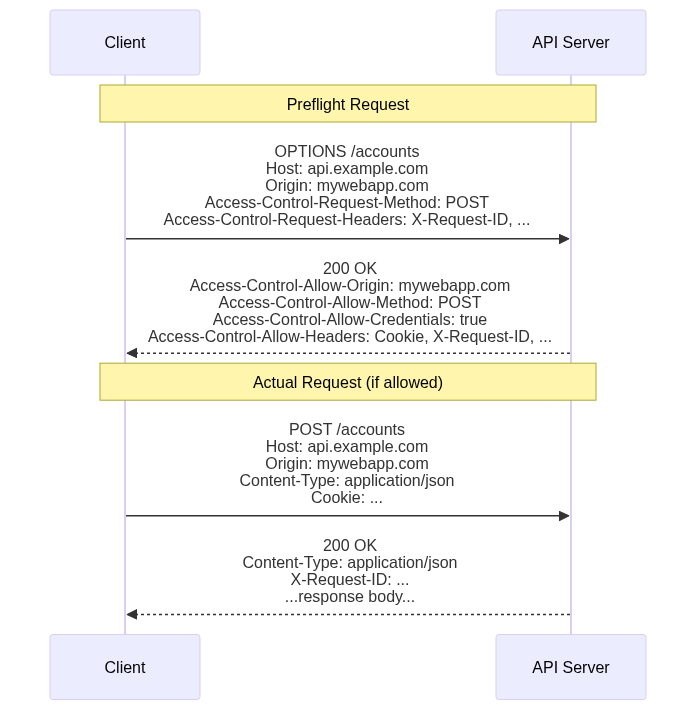

If the client-side JavaScript makes a cross-origin request that doesn’t conform to the restrictive “simple request” criteria, the browser does some extra work to determine if the request should be sent to the server. The browser sends what’s known as a “preflight request,” which is a separate HTTP request for the same resource path, but using the OPTIONS HTTP method instead of the actual request method.

The browser also adds the following headers to the preflight request:

Originset to the origin of the current page.Access-Control-Request-Methodset to the method the JavaScript is attempting to use in the actual request.Access-Control-Request-Headersset to a comma-delimited list of non-simple headers the JavaScript is attempting to include in the actual request.

When the server receives the preflight request, it can examine these headers to determine if the actual request should be allowed. If so, the server should respond with a 200 (OK) status code, and include the following response headers:

Access-Control-Allow-Originset to the value of theOriginrequest header. You can also set it to*but this will block the browser from sending cookies in the actual request, so don’t do this if you are using authenticated session cookies.Access-Control-Allow-Credentialsset totrueif the server will allow the browser to send cookies during the actual request. If omitted or set tofalse, the browser will not include cookies in the actual request. When set to true, setAccess-Control-Allow-Originto the specific origin making the request, not*.Access-Control-Allow-Methodsset to a comma-delimited list of HTTP methods the server will allow on the requested resource, or the specific method requested in theAccess-Control-Request-Methodheader.Access-Control-Allow-Headersset to a comma-delimited list of non-simple headers the server will allow in a request for the resource, or the specific ones mentioned in theAccess-Control-Request-Headers.Access-Control-Expose-Headersset to a comma-delimited list of response headers the browser should expose to the JavaScript if the actual request is sent. If you want the JavaScript to access one of your non-simple response headers (e.g.,AuthorizationorX-Request-ID), you must include that header name in this list. Otherwise the header simply won’t be visible to the client-side JavaScript.Access-Control-Max-Ageset to the maximum number of seconds the browser is allowed to cache and reuse this preflight response if the JavaScript makes additional non-simple requests for the same resource. This cuts down on the amount of preflight requests, especially for client applications that make repeated requests to the same resources.

All of the following must be true for the browser to then send the actual request to the server:

- The

Access-Control-Allow-Originresponse header matches*or the value in theOriginrequest header. - The actual request method is found in the

Access-Control-Allow-Methodsresponse header. - The non-simple request headers are all found in the

Access-Control-Allow-Headersresponse header.

If any of these are not true, the browser doesn’t send the actual request and instead throws an error to the client JavaScript.

CORS and CSRF Attacks

CORS enabled cross-origin APIs, but it also introduced a new security vulnerability: Cross-Site Request Forgery (CSRF). This is the scenario discussed earlier:

- A customer is signed into a CORS-enabled API, which uses cookies for authenticated session tokens.

- The customer is lured to a page on

evil.com - That page contains JavaScript that makes

fetch()requests to the CORS-enabled API. - The browser automatically sends the authentication session token cookie with the request.

- The CORS-enabled API verifies the session cookie, treats the request as authenticated, and performs a potentially damaging operation.

As discussed in the Authenticated Sessions tutorial, the only way a CORS-enabled API can defend against such an attack is to use the Origin request header. This header is set automatically by the browser to the origin from which the HTML page came. JavaScript in that page can neither change this header nor suppress it, so the server can use it as a security input.

CORS-enabled APIs can use the Origin request header in a few ways to protect against CSRF attacks:

- Compare the

Originto a set of allowed origins and reject requests with origins not in the set. - Prefix the session cookie names with a value that is derived from the

Origin: either a hash of the origin value, or an ID associated with the origin in your database. When reading the session cookie from the request, use theOriginto read the particular cookie corresponding to the request origin. This keeps sessions established by different origins separate from each other.

These options are not exclusive—if you track a set of allowed origins, and you want to keep sessions separate per-origin, you can do both. But you should do at least one of these to defend against CSRF attacks.

CORS Middleware

If you want to enable CORS for your API, most web frameworks offer this as a pre-packaged middleware you can simply add to your application with a bit of configuration. For example, in the Python FastAPI framework, it’s as simple as this:

from fastapi import FastAPI

from fastapi.middleware.cors import CORSMiddleware

app = FastAPI()

# List of allowed request origins.

origins = [

"http://localhost:8080",

"https://client.one.com",

"https://client.two.com",

"https://client.three.com",

]

app.add_middleware(

CORSMiddleware,

allow_origins=origins,

allow_credentials=True,

allow_methods=["GET", "POST", "DELETE"],

allow_headers=["Cookie"],

)

In the Rust Axum/Tower framework, it looks like this:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { use tower::{ServiceBuilder, ServiceExt, Service}; use tower_http::cors::{Any, CorsLayer}; // Allows everything, including credentials let cors = CorsLayer::very_permissive(); let mut service = ServiceBuilder::new() .layer(cors) .service_fn(handle); }

The process is similarly easy in all web frameworks. Ask your favorite API tool how to enable CORS with your particular web framework.